On 16th November 1864, the Daily Southern Cross reported that the barque Alfred anchored in New Zealand, having sailed from Cape Town on the 27th September. Included among the 251 passengers were John and Anne Waddoups with their three daughters, Harriet, Mary and Matilda, and Thomas and Mary Ryan with their two sons, Thomas Aylward and Michael Ryan. Along with the passengers, the Alfred was carrying 85 tons of military stores for the government and 5 casks of wine consigned to Messrs. Bucholz and Co. Sea voyages could be perilous and, as we saw on the Edward Oliver, there was often considerable illness and death in the crowded steerage accommodation. This voyage of the Alfred was notable because there were no deaths and a number of passengers wrote a letter thanking the commander of the ship, Captain Decker for transporting them safely to their destination.

“Sir, We the undersigned steerage passengers beg to tender our most sincere thanks to you, and your officers, for the kind and urbane treatment we have always experienced at your hands, and also for the manner in which you have conducted your vessel in bringing us safe, after a long and perilous voyage. We must now conclude, as words we have not sufficient, by wishing you and your officers every happiness and prosperity; and may God bless and protect you all in your dangerous calling is the sincere prayer of all”.

The Waikato immigration scheme was part of an attempt by the New Zealand Government to bring large numbers of immigrants to the North Island. It was felt that the establishment of European settlements would help to consolidate the Government’s position after the New Zealand wars of 1863/64, and would facilitate the development of the regions involved, to the mutual advantage of the general and provincial governments. The cost of these settlements would be recovered from the sale of neighbouring land. To finance the scheme a £3 million loan was to be raised in London, of which Auckland Province would be granted £150,000 for introducing settlers plus £450,000 for surveys and other incidental expenses. Immigrants would be recruited by the Auckland Provincial Government’s agents acting on behalf of the General Government, plus other agents appointed for the purpose. The Government originally intended to bring about 20,000 immigrants to the Waikato, recruiting them from the Cape Colony and the UK, including Ireland. The immigrants would be settled on land available under the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863. ‘Labourers’ (agricultural and railway workers) were offered free passage plus a land grant if they resided on that land for three years. Exact conditions varied slightly between immigrants from the UK and immigrants from the Cape. There was a surfeit of applications from people eager to leave the depressed Cape Colony, however the quantity of land offered to English and Scottish immigrants had to be increased to provide an adequate incentive. Immigrants from the Cape were entitled to five acres and UK immigrants were entitled to ten acres. Both could apply for an additional grant of ten acres, plus five acres for their wives and children over 12 years old, if they repaid half their fare.

By October 1864, the recruiting agents were reporting the successful departure of ships and looking forward to sending more immigrants in the coming months. Their enthusiasm, however, was not matched by the London money market. The New Zealand Loan failed, so there was no money available to continue the scheme. In addition, delays in bringing the New Zealand Settlement Act into operation meant there was little land available on which to settle the immigrants who had already arrived or were on their way, and no land available for sale to defray the expenses of the scheme. At the end of October 1864, the Colonial Secretary in Auckland instructed the agents to suspend all operations until further notice. Approximately 2000 immigrants altogether would now arrive from the United Kingdom and 1000 from the Cape of Good Hope. The General Government wanted the Auckland Provincial Government to take over responsibility for the scheme and the immigrants. For several months, the Auckland Superintendent (who had agreed to administer the scheme on the General Government’s behalf, not as a Provincial responsibility) and the Colonial Secretary exchanged claims and counterclaims against each other. At one stage, the Colonial Secretary suggested that the immigrants be given their land titles at once, rather than after three years; he was reminded by the Superintendent that that would be a direct reversal of the original scheme and that, in any case, the necessary surveys had yet to be completed. Responsibility passed to the newly appointed Agent for the General Government in Auckland, and then to the Provincial Government.

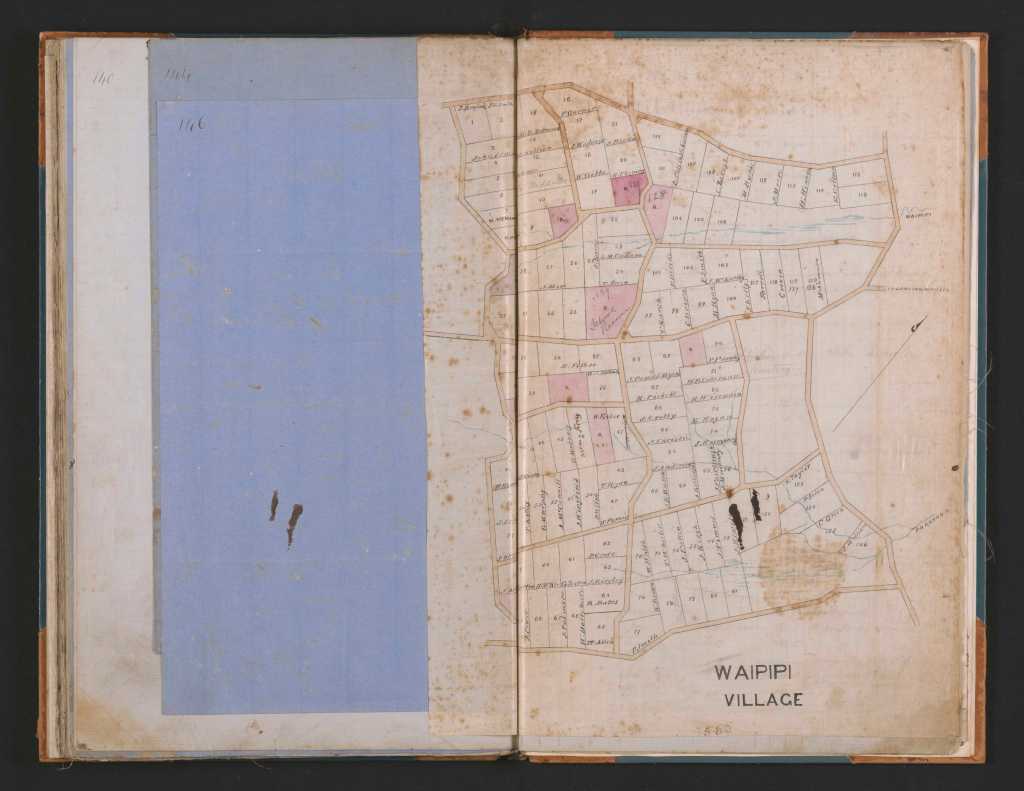

Waipipi was a small settlement on the Awhitu Peninsula. In late 1864 the colonial government had agreed to buy land from Ngāti Te Ata Waiohua, who were considered friendly towards the government. In December 1864 the government overturned the agreement, confiscated the land from the iwi and allocated it to assisted immigrants from the Cape Colony.

Our families on board the Alfred set sail a month before the immigration scheme was abandoned altogether. Upon arrival in Auckland, they were lodged at the Onehunga immigration barracks awaiting their land allocation. On 2nd February 1865 the arrivals from the Alfred, including the Waddoups and Ryan families, were transported across the Manukau and up the Waiuku River to Waipipi, where they were located on their 5-acre allotments. Percy Smith, a surveyor for the Land Purchase Department, noted of the first group from the barque Steinwarder, settled in January, “I saw them landing from the cutters, men, women and children, wading through the mud up to their knees, a very nice experience of their new homes”. Remember the women would have been wearing ankle length skirts and many, like both Mary and Anne, would have been carrying infants. They were bringing with them all their worldly possessions, if they had any at all. Descendants of the Waddoups and Aylward families have lived in Waipipi for the next 159 years and will continue to do so, perhaps for the next 160 years and beyond.

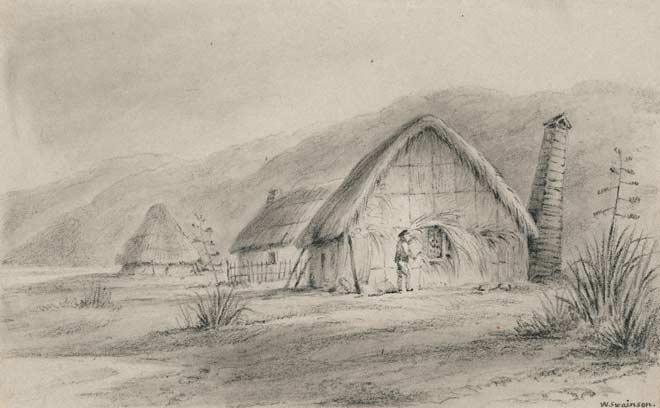

John Waddoups was allocated Lot 17, five acres on Section 4 and Thomas Ryan Lot 48, five acres on Section 4. The new arrivals set up camp in tents and began the task of constructing their new dwellings, initially raupo and harakeke whare. In July the government advanced the settlers money for potatoes and seeds, which was to be paid back after twelve months. The settlement was developed under the supervision of a government appointed immigration officer, Mr Zimmerman who, it appears, abandoned them in 1865 and left them without rations.

Over the next ten years both John Waddoups and Thomas Ryan repaid half their passage money and the seed money plus additional payments and were able to acquire more land. By 1875 John had paid £32.2.9 and acquired an additional 10 acres. Thomas had paid £37.10.0 and acquired an additional 15 acres.

A school, with a teacher, operated from 1865 although the building wasn’t erected until 1874. Education would have been very important to the immigrants many of whom, including John and Anne Waddoups, and Thomas and Mary Ryan, could neither read nor write.

As the settlement flourished the families grew. In November 1867 the youngest Waddoups daughter, Georgina, was born. By 1877 the girls were beginning to make their own way in the world. In August 1877 Harriet married Aaron Griffiths in Thames. Between 1878 and 1900 they had 11 children, Harriet, Hannah, Jack, Ruth, Ted, Charlotte, Frank, Ernie, Eunice, Frederick and Leo

In 1877 Mary married Frederick Kaina, “in the dwelling house of her father, John Waddoups at Waipipi”. Frederick, who was born in Prussia (now Germany), had also travelled as a child, from the Cape on board the Alfred. Mary and Frederick had one son, also Frederick. Frederick senior died in 1879 and Mary remarried Lawrence Hanlon. Mary and Lawrence had four children, Lawrence, Henry, Albert and Mary.

Georgina, the youngest, seems to have been quite independent. In August 1886, aged 19, she was working at the Manukau Hotel, Onehunga, possibly as a barmaid. On August 20th there was a bit of a to-do at the hotel and the proprietor was assaulted by the owner of a shop across the road. Charges were laid and Georgina was called to give evidence for the prosecution.

In 1889, aged 22, Georgina gave birth to a son, Harry Alfred, however the father was not named on the birth certificate. In May 1890 she travelled to Australia with Harry on the steamer Jubilee. Also on board was one Alfred Tointon, aged 42. Alfred was wanted by the police on a charge of desertion, having left a wife and four children in Wellington. Between 1891 and 1899 Alfred (now known as Taunton) and Georgina had four more children in Lithgow, New South Wales: Francis, Dorothy, Ruth and Georgina.

There is quite a bit more to be told about these Waddoups sisters and I will write a separate story about them.

In 1875/76 typhoid was widespread in New Zealand, resulting in around 600 deaths across the country. In June 1876 thirteen-year-old Michael Ryan contracted the disease. According to an account by his grandsons, Thomas Aylward said that Michael became very weak and that he, a sixteen-year-old, was dispatched on horseback to fetch the doctor. There was no doctor at Waipipi, and he had to ride overnight via the Bald Hill bridle track to Pukekohe. By the time he returned the next day with the doctor, Michael was dead. He was buried in the Waipipi cemetery on 23rd June 1876.

On 2nd August 1879 Thomas Ryan died, aged 63, in Auckland hospital. Curiously, Thomas’ death was registered twice, once at the hospital where the cause of death was registered as heart disease and the informant was James Nash, the hospital messenger, and then again from Waipipi where his cause of death was listed as consumption and the informant was his stepson, Patrick. It’s a long journey from Waipipi to Auckland hospital Thomas would have been transported by barge to Onehunga and then by horse and gig to the hospital. Possibly the doctors believed he might survive his illness and so the journey would be worthwhile. Probably, when the family were informed of his death, they didn’t realise that the hospital had already registered his death and thought that they needed to do it. The hospital probably recorded the correct cause of death. This is the first we hear of Patrick Aylward, the first son of Mary Spain and Michael Aylward, who was left behind in Ireland when Mary and Michael emigrated to Capetown, being in New Zealand. Patrick may have arrived earlier in 1879 and I’ll come back to him when I tell more of Thomas’ and Matilda’s story.

Digging a bit further into James Nash, the hospital messenger, I learned that this job is just what it sounds like – James carried messages around the hospital. So, when Thomas died, James would have been asked to carry a message informing the doctor in order that the death could be formally recorded. I became a little curious about James Nash. In June 1879, according to a police report, he had had a macintosh and a pair of leggings stolen from his lodgings and as a result he had been forced to walk to and from the hospital in the rain and had caught a severe cold. The thief, who was a habitual criminal, was sentenced to six months in prison with hard labour. James died in 1898 aged 82, so at the time of Thomas’ death he would have been 71. There was no national superannuation in those days.

The following obituary for Thomas Ryan, appeared in the Auckland Herald on 16th August. He appears to have been very well regarded in the district.

“I regret to have to record the death of one of our highly-respected settlers – Mr Thomas Ryan, Waipipi. The deceased was a native of the parish of Ballycallan, County Kilkenny, Ireland, and colour-sergeant of the Waipipi volunteers. He formerly belonged to the 87th Regiment. During his illness, which he bore with Christian fortitude, he was regularly attended by the Very Rev Dr McDonald at Waipipi, and in Auckland, Father Walter McDonald, whose kindness to the deceased will always be remembered with gratitude by his family and the people of the district. Mr Ryan’s death has cast quite a gloom over the settlement, as he was a general favourite, especially with the youth. All that medical skill, coupled with the unremitting attention of his sorrowing wife, could effect, appeared never wanting during his protracted illness. His funeral took place on Tuesday the 5th instant, and was largely attended by the settlers of Waipipi, Waiuku, Whiriwhiri, Maioro, Kohekohe, and Pukekohe. The funeral service was performed in a very impressive manner at the Waipipi Catholic Church, and at the graveside by Dr McDonald, who offered the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass for the repose of his soul on the morning of interment. The great respect in which the deceased was held appeared manifest from the numbers who attended the funeral, notwithstanding the inclemency of the weather. The Catholics of Waipipi have lost one of their best friends in the late lamented Mr Ryan. It was only a short time since he had been instrumental in raising a handsome sum towards some necessary improvements in the Waipipi church, and he was always foremost in every work appertaining to the interests of religion.”

On 29th January 1894 Matilda Waddoups married Thomas Aylward, son of Mary Ryan and stepson of Thomas Ryan. Between 1894 and 1908 Thomas and Matilda had 9 children, the oldest of whom was my grandmother, Mary Winifred. I’ll return to Thomas and Matilda’s story separately.

On 21st October 1895, John Waddoups died, aged 72. According to his will he left his farm to his son in law, Thomas Aylward, which reportedly caused a rift among the Waddoups sisters. John is buried in the Waipipi cemetery alongside Anne who died 17th September 1902, aged 81.

On 8th February 1917 Mary Ryan died from a stroke, aged 85. She had lived a long and a hard life from her birth in Woodford, Ireland, leaving her son Patrick when she migrated to South Africa, the loss of her first husband, Michael, the death of her thirteen-year-old son, Michael Ryan, and then the untimely death of her second husband, Thomas Ryan. I have no photos of her but, in my mind, she is a strong, kind, small, dark-haired woman, the beloved grandma of my grandma Mary, who always referred to her as Granny Ryan.

Other stuff you might find interesting:

New Zealand Settlements Act 1863

Deed of Settlement between the Crown and Ngāti Tamaoho

Ngāti Te Ata Cultural Assessment report

A short history of land alienation in South Manukau